Case Study: Solid-State Illumination - Light Engines for Photoresponsivity Characterization

Artificial light sources are essential for the characterization of photoresponsivity of photovoltaic devices and solar fuel cells. Traditionally, xenon arc or tungsten-halogen lamps, equipped with sources with spectral outputs that are not readily amenable to controlled adjustment and with relatively short operating lifetimes, have been used for this purpose. Consequently, they are now being superseded by solid-state illuminators based on arrays of LEDs and/or diode lasers. This case study provides examples of the utility of solid-state illumination sources for characterization of photovoltaic devices and solar fuel cells and outlines some of their inherent technical advantages.

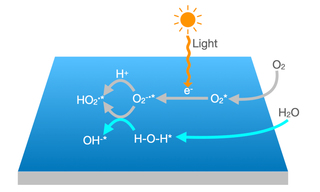

In the course of development of halide perovskites (HP) as low-cost, high-efficiency photovoltaic materials, a team of researchers at the University of Washington in Seattle (1) used optical transmittance measurements to quantitatively assess the effects of oxygen, humidity and illumination flux on the degradation of a prototypical HP, methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3). Sample illumination was supplied by a RETRA Light Engine (Lumencor, Inc., Beaverton, Oregon USA), providing incident photon fluxes of 1–10 suns (1 sun = 100 mW/cm2). Two predominant modes of HP degradation were identified — dry photooxidation (DPO) occurring in the absence of vapor-phase water and a water-accelerated photooxidation (WPO) pathway (Figure 1). WPO proceeds faster than DPO, even at a very low humidity. These results have significant implications for the design of both encapsulation schemes for halide perovskite photovoltaics and accelerated testing protocols for service lifetime prediction.

In contrast to photovoltaic technologies, which seek to generate electricity directly from sunlight, the goal of artificial photosynthesis is to convert sunlight into stored chemical energy. This can be accomplished by splitting of water into hydrogen fuel and oxygen in photoelectrochemical cells (PEC). Researchers at the University of North Carolina (UNC) have described a second-generation, dye-sensitized PEC that achieves greatly enhanced visible-light–driven water splitting efficiencies. Performance evaluation was carried out using the 445 nm light output from a SPECTRA Light Engine (Lumencor, Inc., Beaverton, Oregon USA) (2). More recently, another UNC research team used a SPECTRA X Light Engine to determine the spectral dependence of hydrogen generation by silicon nanowire based PECs [3].

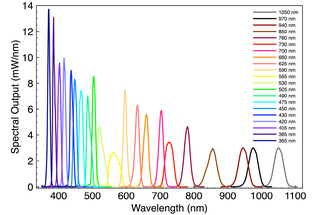

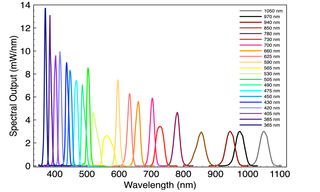

In addition to their consistent and reliable performance, the utility of solid-state illuminators for photoresponsivity testing derives from their modular design and programmable electronic controls. For example, broad spectral coverage can be obtained from arrays of LEDs. The relative output intensities of the LED elements in an array in which intensity is well controlled, and predictable due in large part to its linear behavior, enables synthesis of user-specified spectral distributions (Figure 2). The spectral outputs of a MAGMA Light Engine (Lumencor, Inc., Beaverton, Oregon USA) incorporating 21 individually addressable LED light sources, range from 365 nm to 1050 nm. The LED outputs are merged into a common optical train directed to the light output port on the front panel and may be initiated in parallel or serial under the control of a single, onboard microprocessor. Adjustment of the relative output intensities of the 21 elements of the LED array enables synthesis of user-specified spectral distributions.

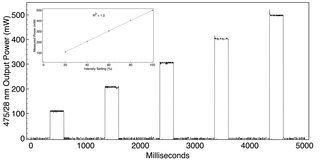

Photocurrent generated per incident unit optical power is a key performance metric for both photovoltaic materials and photoelectrochemical fuel cells. Solid state illuminators provide the precise control of incident optical power required for accurate characterization of these dose-response relationships. The demonstrable capacity for controlled light output derives from on/off switching with millisecond precision and microprocessor-enabled linearization of output power. Figure 3 shows the filtered (475+/-14 nm) LED output from a SPECTRA Light Engine (Lumencor, Beaverton, Oregon, USA) detected by a calibrated photodiode. Output power is programmatically increased by 20% for each successive 250 ms pulse. The control response is precisely linear as indicated by the R2 value of 1.0 (inset).

The precise and reproducible performance of solid-state lighting like that of these Lumencor Light Engines enables characterization of photovoltaic devices and solar fuel cells. The ability to precisely control the illumination optical output in terms of spectral content, spectral breadth, linearity, and temporal control offers unique advantages over other sorts of solid-state lighting an enables inherent technical advantages for these sorts of photochemical applications both in descrete experimental protocols and for the implementation of large scale production and quality control.

Figure 1. Dry photooxidation (DPO) and water-accelerated photooxidation (WPO) pathways generating hydroperoxyl radical, superoxide radical and hydroxyl ion reactive oxygen species that give rise to halide perovskite decomposition.

Figure 2. Spectral output of a MAGMA Light Engine (Lumencor, Beaverton OR) incorporating 21 individually addressable LED light sources, ranging from 365 nm to 1050 nm, under the control of an onboard microprocessor. The LED outputs are merged into a common optical train directed to the light output port on the front panel. Adjustment of the relative output intensities of the 21 elements of the LED array enables synthesis of user-specified spectral distributions.

Figure 3. Filtered (475+/-14 nm) LED output from a SPECTRA Light Engine (Lumencor, Beaverton, OR) detected by a calibrated photodiode. Output power is programmatically increased by 20% for each successive 250 ms pulse. The control response is precisely linear (inset).

- May 18, 2023

- MAGMA Light Engine Data Sheet(opens in new window)

- RETRA Light Engine Data Sheet(opens in new window)

- SPECTRA X Light Engine Data Sheet(opens in new window)

- SPECTRA Light Engine Data Sheet(opens in new window)

- Case Study: Solid-State Illumination- Light Engines for Photoresponsivity Characterization(opens in new window)

- [1] Water-accelerated photooxidation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite. TD Siegler, WA Dunlap-Shohl, HW Hillhouse et al., J Am Chem Soc (2022) 144:5552−5561(opens in new window)

- [2] Visible photoelectrochemical water splitting into H2 and O2 in a dye-sensitized photoelectrosynthesis cell. L Alibabaei, BD Sherman, TJ Meyer et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2015) 112:5899–5902(opens in new window)

- [3] Water splitting with silicon p-i-n superlattices suspended in solution. TS Teitsworth, DJ Hill, JF Cahoon et al., Nature (2023) 614:270–274(opens in new window)