White Paper | Multimode Lasers Revisited: Optimized Performance and Value for Confocal and Super-resolution Microscopy

Introduction

Lumencor has been challenging conventional strategies regarding illumination for light microscopy since its founding in 2006. At the time, the competitive landscape for solid-state illumination for light microscopy was primarily focused on LEDs as potential replacements to white light arc lamps. LEDs were thought to under perform on optical power and spectral range, particularly in the notorious “green gap” (500-600nm). However, Lumencor changed the pervading thoughts regarding solid-state solutions for light microscopy in no small part due to a patented light pipe technology which outperforms any green LED in both optical power and brightness. Multi-source LED and light pipe alternatives to spectrally limited white light LEDs became a widely accepted solution, now commonly referred to as SOLA Light Engines. Similarly, color-selective illumination solutions were addressed with well matched LED or Light Pipe emission and integrated bandpass filters to hone the wavelengths of interest for maximal brightness and minimal background. As the field of light microscopy continues to advance increasingly complicated methods with confocal and super-resolution techniques, lighting manufacturers have to find new lighting solutions.

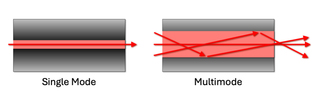

New light microscopy techniques with esoteric names such as MERFISH (Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization), STORM (Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy), OPS (Orthogonal Polarization Spectral Microscopy) and SIM (Structured Illumination Microscopy) emerge on what can feel like a monthly basis. For these new applications, light manufacturers continue to rely on single mode lasers. Single mode lasers have been well characterized since their first commercial availability in the early 1980s. These lasers provide the precision, stability and focus needed in light microscopy - especially in high resolution and fluorescence-based techniques. Output beams are characterized by very narrow spectral width, high spatial coherence and stable, Gaussian-shaped beam profile (see Figure 1). Narrow bandwidths of specific wavelengths support high spectral precision and minimize crosstalk. High spatial coherence enables tight focus for high resolution. Stable beam profiles support uniform illumination for better image quality. Minimal mode hopping or noise results in consistent imaging and quantitative accuracy. This makes single mode lasers pure, precise and coherent light sources, applicable to high performance microscopy techniques.

Figure 1: A schematic illustrating laser light propagation and fiber exiting in two scenarios: single mode and multimode laser configurations.

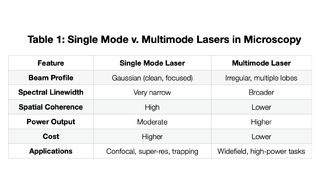

Historically, single mode and multimode lasers have fallen into two different application types. The former in support of confocal, super-resolution and trapping microscopy techniques. The latter in broader use for widefield, high-power light microscopy. In fluorescence microscopy, fluorophores emit most efficiently when excited at specific wavelengths of maximum absorption. With the pure, stable and narrow wavelength excitation of single mode lasers, they reduce spectral bleed through and support better signal-to-noise. In the case of confocal microscopy, these attributes help reject out-of-focus light improving clarity and 3D reconstruction. In super-resolution microscopy like STED Stimulated Emission Depletion Microscopy), PALM (Photoactivated Localization Microscopy) or STORM, the reliance on precise control over excitation and depletion of fluorophores requires a stable, coherent light source. Such precision comes at a significantly higher cost. As such, multimode lasers have been less commonly implemented in high-precision microscopy, despite having excellent utility when high power or cost-management is more compelling than beam quality. Engineers at Lumencor asked: are there attributes of single mode lasers that could be satisfied with lower cost multimode lasers while still supporting the lighting requirements for advanced light microscopy techniques?

Lumencor recognized that multimode lasers in widefield fluorescence microscopy support the illumination of large fields of view where precise beam shape and beam focus is not critical (Table 1). Their high power allows for strong excitation of fluorophores across the entire large target area. Multimode lasers are typically significantly less expensive than single mode lasers which becomes paramount when the cost of illumination rivals the cost of the microscopy hardware accessories as can be the case in confocal imaging. With single mode laser lifetimes of only a few years, replacement costs are a real and ongoing burden. While single mode lasers are typically coupled by narrow bore, single mode fibers, multimode lasers may be implemented in advanced microscopy techniques via multimode optical fibers matched to the étendue of the receiving instrument. They can also be implemented with free-space or projections optics depending on the recipient angle and area of the instrument optics. Efficient light delivery into multimode fibers is often convenient and simple to implement. In the case of photobleaching or photo-stimulation, high optical power is required over spatial precision. Multimode lasers can deliver high-intensity light sufficient for bleaching or activation of fluorescent proteins. Historically manufacturers of confocal microscope accessories, like spinning disk and super-resolution modalities, limited the integration of lighting to single mode lasers. Lumencor’s multimode laser illuminators, the ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engines, break through this segmentation with as many as seven solid-state lasers housed in a robust, turnkey box. The ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engines have demonstrated that the broader beam profiles and lower spatial coherence of multimode lasers can be engineered in support of numerous advanced light microscopy applications. Overcoming the multimode laser constraints of reduced image clarity, focal precision and spectral purity, the ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engines are elevated to the realm of applications previously limited to single mode lasers. Examples of spinning disk confocal, STORM and SoRa (Super-resolution by Optical Pixel Reassignment) imaging with ZIVA and CELESTA, multimode laser products, are described herein.

Stability of Multimode Laser Light Engines

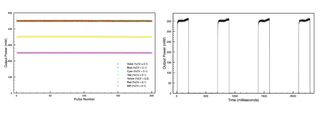

The output power stability of lasers is a critical specification when considering optimization of lighting for advanced microscopy techniques. The materials used in laser sources determine the performance parameters. It is essential that both manufacturers and researchers have methods to ensure stability of the light output during the lifetime of the Light Engine. The Consortium for Quality Assessment and Reproducibility for Instruments and Images in Light Microscopy (QUAREP-LiMi) have released guidelines for measuring the stability and linearity of lasers for microscopy [1]. Each ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engine is tested following the QUAREP-LiMi guidelines for stability and linearity. Diode lasers such as those used in the ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engines have different operational conditions compared to traditional single mode lasers, and the performance is tuned specifically to the application. Particularly, lasers with outputs in the “green gap” (500-600nm) can demonstrate suboptimal performance when used outside the recommended operational conditions. As such, ZIVA and CELESTA quality control testing focuses on the application specific uses when considering output stability. Pulse-to-pulse stability is the key metric in most advanced microscopy techniques for routine maintenance of systems. Both the average output power for each wavelength and the coefficient of variation (%CV) are measured for the ZIVA Light Engine during manufacturing (Figure 2). Each individual pulse is also considered during quality control to ensure optimal stability within each data point of an experiment. Testing protocols are provided to researchers so that stability can be monitored during the lifetime of the Light Engine.

While each the CELESTA and ZIVA Light Engine are manufactured to a unique specification, several overriding guidelines ensure optimal stability during use. Laser warm-up prior to acquisition dictates the lasers are ON for at least 60 seconds at 0% to “pre-condition” the laser. This warm-up period thermally equilibrates the sources and minimizes fluctuations due to thermalization during data collection. Each laser’s recommended operational power settings reside above a threshold value, typically above 5% or 10%, which represents its minimum pump power (the energy needed for it to produce a coherent laser beam when the optical gain from stimulated emission exactly balances the losses due to absorption, scattering, and mirror loss in the laser cavity.) Exceeding this threshold shifts output from spontaneous to stimulated emission dominance. Below this threshold, output is weak; above it, the output efficiency dramatically increases, creating a strong, stable beam. Further, ZIVA and CELESTA Light Engines perform optimally in pulsed power modes, as opposed to continuous mode. It is not recommended to use continuous output and/or PID mode in standard operating conditions. However, optimal continuous mode use and PID operation is available in customized protocols with Lumencor’s assistance.

Figure 2: ZIVA Light Engine Stability Data. Average power output per pulse across 200 pulses is displayed for all lasers within an exemplary Light Engine (left). Note: The data of the Blue, Cyan, Teal, Red and NIR sources overlap in the displayed graph. The coefficient of variation (%CV) verifies pulse-to-pulse robustness and stability. Individual consecutive pulses for the Yellow laser show limited variation in pulse shape between pulses (right).

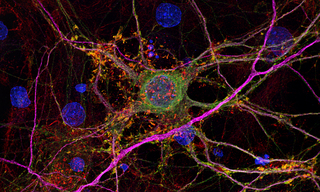

Yokogawa Confocal Spinning Disk CSU

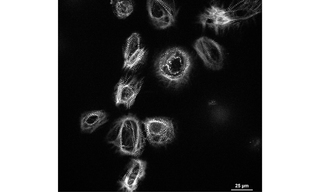

The Yokogawa CSU is a spinning disk confocal accessory which can attach to conventional widefield fluorescence microscopes to perform optical sectioning at high speed. It enables real-time, fast imaging compared to point scanning confocal [2]. Spinning disk confocal reduces photobleaching and phototoxicity relative to point scanning confocal because the excitation light is distributed over many simultaneous beams rather than scanning a single point. It retains confocal sectioning, rejecting light from out-of-focus planes, by means of pinholes in the disk. The Yokogawa CSU uses a dual disk system with a micro-lens array to increase light throughput. The excitation light through the pinholes is scanned over the sample, and the emission light is collected back through one set of pinholes and imaged on a sensitive camera (e.g. EMCCD or sCMOS). The emission light passing back through the pinholes creates confocal images by rejecting out of focus emission light. Parallel scanning allows for fast imaging that is ideal for live samples and other applications where photobleaching and phototoxicity are concerns (see Figure 3).

Historically, the Yokogawa CSU has been fiber-coupled to single mode lasers. Since many pinholes are scanned in parallel, the requirement for lighting becomes high intensity light distributed uniformly across the entire field of view. The ZIVA Light Engine has been designed to directly deliver a uniform, high-intensity beam to the Yokogawa CSU. The high power output from the ZIVA Light Engine ensures that both dim and bright samples can be imaged quickly and efficiently with minimal differences from traditional single mode lasers.

Figure 3: In vitro, cultured cardiomyocyte spheroids are imaged with CSU-W1 to demonstrate the advantage of gentle, uniform confocal imaging via Yokogawa spinning disk module (200 timepoints at 100 μs frequency) with ZIVA’s 577 nm laser, as opposed to laser scanning confocal techniques. The sample is remarkable in that investigators found it could not be resolved on the core facilities’ laser scanning confocal instrument. The regenerating cardiac tissue is imaged in the attempt to identify novel therapies for cardiovascular disease. Fast acquisition video rate imaging shows cell volumes and long lived, functioning cells despite the photonic interrogation.

Super-resolution via Optical Reassignment (SoRa)

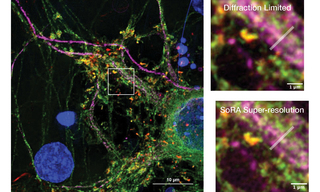

Super-resolution via optical reassignment (SoRa) is a super-resolution technique that is offered as a modification accessory to the Yokogawa CSU-W1. Conventional fluorescence microscopy resolution is limited by the diffraction limit of light, typically 200-300 nm depending on the wavelength. Structures with features smaller than the diffraction limit cannot be resolved in widefield fluorescence microscopy. In the CSU-W1 SoRa, an additional set of micro-lenses is added to the pinholes on the emission side and a matched tube lens is inserted into the light path to optically reassign the emission light. Effectively, each point of emitted light behaves as if viewed through a much smaller pinhole leading to a smaller effective point spread function (PSF) without sacrificing signal brightness [3]. The result of the SoRa spinning disk is ~1.4X improvement of lateral resolution compared to widefield or traditional spinning disk. When combined with post-acquisition deconvolution, there is ~2X greater resolution (see Figure 4). The CSU-W1 SoRa maintains the advantages of spinning disk microscopy including high speed imaging and low phototoxicity. Integration of the ZIVA Light Engine is as seamless as the standard Yokogawa CSU spinning disk. Uniform, high-power illumination from the direct coupling adapter creates ideal lighting to suit the requirements of SoRa.

Figure 4: Cultured mouse neurons captured on a Yokogawa CSU-W1 SoRa with post-acquisition deconvolution demonstrates super-resolution imaging with the ZIVA Light Engine (left). Matched images from the same field of view (white dashed box; left) demonstrates the increase in resolution with the SoRa disk compared to the standard 50 µm disk in the Yokogawa CSU-W1 (right). The Gray Level vs. Distance plot (right) quantitatively illustrates the intensity profile differences—measured along the white line in the images above—between the SoRa-enhanced and standard Yokogawa CSU-W1 captured images.

Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM)

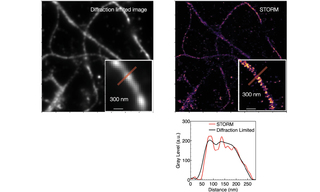

STORM (Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy) is a type of super-resolution fluorescence microscopy that overcomes the diffraction limit of light (~200 nm) to achieve nanometer-scale resolution, typically on the order of 20–30 nm (see Figure 5). STORM relies on stochastic activation and localization of individual fluorescent molecules. It avoids the diffraction limit by imaging only a sparse subset of fluorophores at any given time such that multiple fluorescent molecule PSFs do not overlap.

Target structures like proteins or cellular features are labeled in STORM imaging with specific fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy5, Alexa Fluor 647), that can toggle between dark and fluorescent states. A small, random subset of fluorophores is activated at a time using a high-power, high-irradiance laser. Only a sparse distribution of molecules emits light, ensuring PSFs do not overlap. The positions of these individual fluorophores are determined with nanometer precision by fitting their PSFs to a 2D Gaussian distribution. This is the core of the “reconstruction”. The active fluorophores are turned off (or bleached), and another subset is activated. The process is repeated thousands of times, gradually building up a map of molecule positions. All the localized positions from many hundreds to thousands of images are combined to form a high resolution image of the structure. Applications include nanoscale imaging of cellular structures (e.g., cytoskeleton, membranes, organelles); protein clustering and interactions; neuroscience and synapse structure; virology and bacteriology. While single mode lasers have been the traditional light source for STORM, multimode lasers are capable of delivering the amount of light needed to convert the fluorescent molecules in a sample to a dark state [4]. The CELESTA Light Engine coupled with a critical epi-illuminator is capable of delivering the light necessary for STORM imaging, and offers a lower cost alternative with greater emission spectral output compared to single mode lasers.

Figure 5: Actin, spectrin and associated molecules form a membrane-associated periodic skeleton that plays an important role in the regulation of neuronal function and dysfunction. Diffraction-limited (left) and STORM (right) images of axonal MPS illustrate the resolution improvement of STORM techniques. The Gray Level vs. Distance plot (right) quantitatively illustrates the intensity profile differences—measured along the red line in the zoomed-in images above—between the STORM image and the conventional diffraction-limited fluorescent image.

Conclusion

Lumencor has played a pivotal role in the development of lighting solutions for life science research powered by microscopy. The introduction of light pipe technology effectively solves the “green gap” in a critical spectral window historically underserved by LEDs for fluorophores of import throughout fixed and live cell imaging. The establishment of LED illuminators set a precedent for solid-state replacements of white light arc lamps with spectral breadth, brightness, stability, longevity and reproducibility. More recently, Lumencor has engineered multimode lasers in Light Engines that challenge technical laser lighting paradigms once relegated to the use of single mode lasers. Such Light Engines host an array of lasers throughout a broad spectral range (400 - 800 nm), and feature high brightness (~5000 mW/mm2), fast switching times (100 µsec) and excellent short term (<1% peak to peak noise over 10 sec) and long term (<2% peak to peak noise over 25 min) stability. As well, in labs where space is precious the small foot print and compact volume (on the order of a toaster as opposed to entire laser table of components) cannot be undervalued. Turnkey operation, no service, no replacement parts, and long lifetime ensure both ease of use and high value. While very much a function of operational use scenarios, such laser Light Engines readily provide more than 70% of their initial optical output for as long as five to ten years of use, with no maintenance and no replacement parts. Multimode lasers are both less expensive and longer-lasting than their single mode counterparts. Further, Lumencor’s multimode laser products (CELESTA and ZIVA Light Engines) offer illumination with exceptional spectral, spatial, and temporal control that has become synonymous with the brand.

Applications described herein, namely Yokogawa CSU-W1 spinning disk and super-resolution microscopy techniques like SoRa and STORM, confirm that CELESTA and ZIVA Light Engines support high-speed imaging within the time scale of typical biological cellular events. As well, they are compatible with super-resolution techniques that enable imaging of cellular features with dimensions below the diffraction limit of light, < 200 nanometers. CELESTA and ZIVA are configurable with up to seven individually controlled lasers with switching time between laser wavelengths on the order of 100 µsec. They provide deserving imaging applications the capacity to visualize multicolored samples using today’s most advanced microscopy techniques, including SIM, TIRF (Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence), MERFISH, PALM, STED, and others. In this time of tight budgets and economic uncertainty, given the inevitable lifetime limitations of typical single mode lasers (on the order of 2–3 years), users now have illumination alternatives from Lumencor that bode well for the proliferation of even the most esoteric microscopy techniques and the democratization of today’s most capable optical imaging hardware.

- Jan 20, 2026

- Azuma T, Kei T. Super-resolution spinning-disk confocal microscopy using optical photon reassignment. Opt Express. 2015;23(11):15003-15011. doi:10.1364/OE.23.015003(opens in new window)

- Jang H, Li Y, Fung AA, et al. Super-resolution SRS microscopy with A-PoD. Nat Methods. 2023;20(3):448-458. doi:10.1038/s41592-023-01779-1(opens in new window)

- Stehbens S, Pemble H, Murrow L, Wittmann T. Imaging intracellular protein dynamics by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2012;504:293-313. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-391857-4.00015-X(opens in new window)

- Illumination Power, Stability, and Linearity Measurements for Confocal, Widefield and Multiphoton Microscopes.(opens in new window)